How to get down (and up) to your own beat.

Your body, a bit like a jazz band, has its own groove... a deep-down, inbuilt beat that jams with the melody of the birds and the perpetual motion of the sun. It’s our Circadian Rhythm, aka ‘body clock’, an internal timer that registers light and regulates hormones, digestion and temperature accordingly. So, when we harmonise with our own metronome and have a healthy relationship with the rise and fall of the sun, we naturally will feel better, think better and sleep better.

What are Circadian Rhythms?

Circadian Rhythms were first described in 1729 by French Astronomer Jean Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan after he noted the leaves of a mimosa plant opening in the morning and closing in the evening… even in a dark room. In the centuries since, scientists have learned that the same 24-hour cycle orchestrates physical, mental, and behavioural changes across the tree of life, from animals to plants and even microbes.

Light and dark are the biggest triggers of circadian responses; however, stress, temperature, physical activity, and nutrition also play key roles depending on the species. But just because we use the same clock as an owl, doesn’t mean we should mimic its schedule. It goes without saying that rhythmic responses are species-dependent, but given some variations, don’t worry if you’re a ‘hoot’ after midnight, but more on that later. In evolutionary terms, these behavioural rhythms have been preserved and honed over time; as they say, the early owl catches the mice! (Cermakian & Boivin, 2003).

The Human Clock

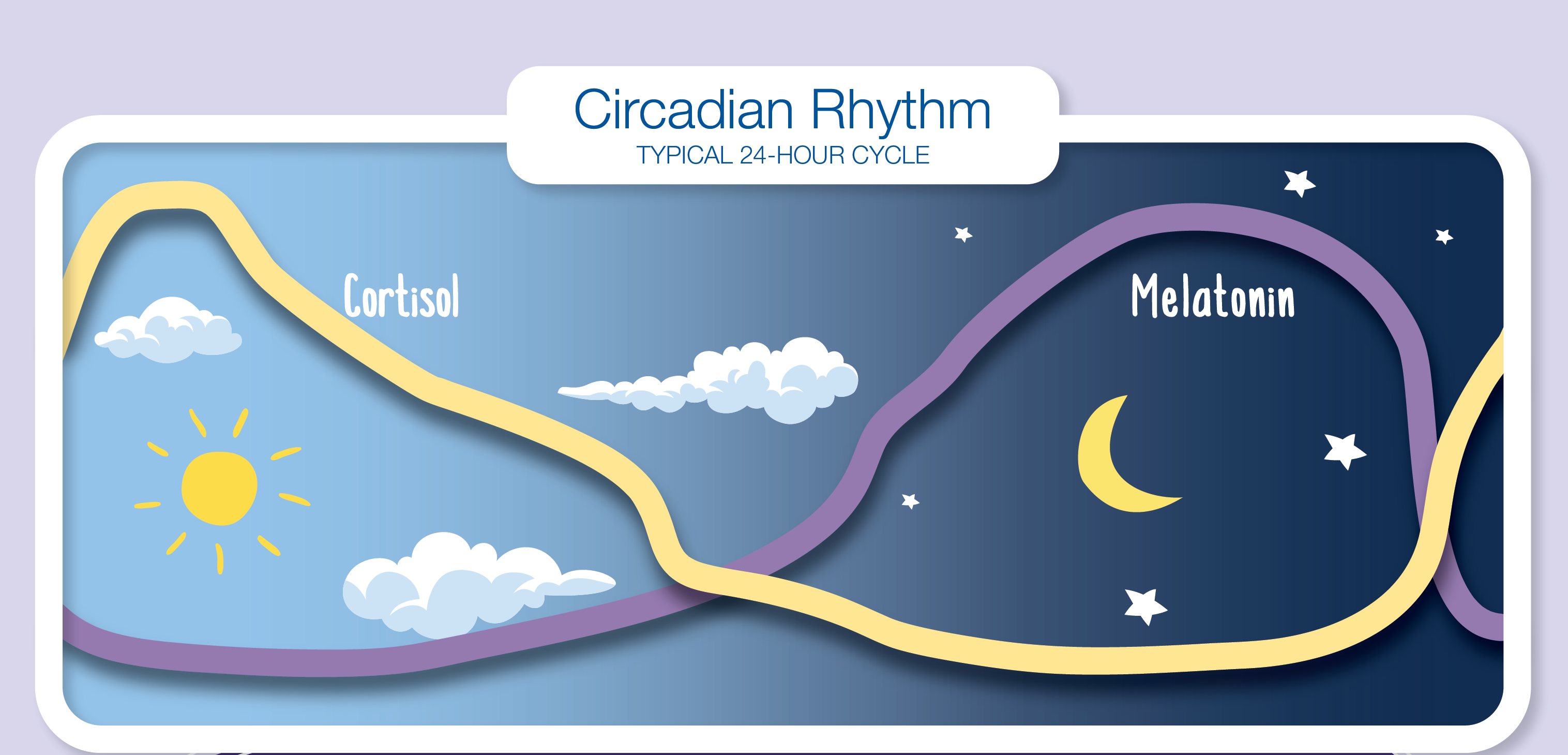

You might be familiar with the human circadian rhythm; after all, it governs your daily routine, but deep in your cells, it is an inbuilt mechanism that controls your hormone release, body temperature, digestion, appetite, and sleeping patterns. This clock is less of a metaphor and more of a protein timer, but it is a bit different to the one on the front of your oven. Proteins in our cells create a 24-hour cycle by turning each other on and off in a specific rhythm commanded by the Suprachiasmatic Nucleus or, more legibly, the SCN). This collection of 20,000 nerve cells in our brain observes light signals and resets this cycle daily, acting like a master clock (Reppert & Weave, 2002). This helps regulate sleep by releasing melatonin at night, when there isn't much light to make us sleepy. Conversely, morning light reduces melatonin levels and increases cortisol, helping us to get up in the morning and stay awake (Duffy & Czeisler, 2009).

Our trusty SCN has evolved alongside us and helped us to survive by aligning our important activities with the daylight, when our eyes can see and settle us down with the setting of the sun.

Missing the Beat

Modern life's demands often require us to shift our sleeping patterns and adjust our circadian rhythms. Extended sleep disruptions, however, can have long-term consequences. Here are several habits to look out for:

Oversleeping

Although it’s nice on occasion, consistent schedules support optimal circadian function. Variations, even on weekends, can lead to ‘jet lag’ - akin to the effects of changing time zones (Wittmann et al., 2006).

Jet lag

Actual jet lag from crossing time zones can upset the body's internal clock as it adjusts to new light-dark cycles, a process that can take several days (Waterhouse et al., 2007).

Screen Time

Exposure to light from screens in the evening is thought to inhibit melatonin production, which delays our exposure to light from screens in the evening is thought to inhibit melatonin production, which delays our sleep onset (Chang et al., 2015).

Night Shifts

Working night shifts can lead to “shift work disorders”, which come with an increase in the risk of chronic conditions like cardiovascular disease (Straif et al., 2007). Despite this, some thrive under these conditions.

Menstrual Cycles

Hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle can affect sleep patterns. Some biological women can experience disrupted sleep before their menstruation, however, this can often be alleviated by light therapy/taking in natural daylight (Baker & Driver, 2007).

Keeping in Time

When disrupted, our Circadian Rhythms can lead to various mental and physical health issues. Having hormones released at the wrong time of day can misalign insulin levels, leading to diabetes and overeating/obesity (Bass & Takahashi, 2010). Depression is also a common side effect of our rhythms being out offbeat, and under-sleeping can often cause anxiety and paranoia (Turek et al., 2005).

Respecting circadian rhythms is crucial for maintaining health and wellbeing. As we continue to navigate our busy modern lives, understanding and aligning our schedules with our own biological clocks (and chronotypes) can offer significant health benefits.

Sleep Hygiene

Evolution has fine-tuned our Circadian Rhythms to align with cycles in the natural world, but many of us are far removed from our hunter-gatherer genesis.

When modern lifestyles clash with our natural rhythms, we need to find ways to mitigate the impact of bad sleep. This brings us to sleep hygiene, and no, that doesn’t mean showering before bed. Despite our different rhythms, there are a few things we can do to make our bedtime easier.

Timing

Some people can sleep whenever they want; the rest are jealous of the fact. Maintaining consistent sleep schedules is the best bet for most people, and yes, even on weekends. This is not practical for some lines of work, but those who have irregular sleep patterns should try gradual changes, such as waking up 15 minutes earlier each day. This can help realign our internal clock over time without a sudden shock (Sharkey et al., 2012). Maintaining a regular sleep-wake cycle is always the best way to reinforce the body's natural rhythms.

Light

The impact of light on Circadian Rhythms is particularly relevant. Blue light, which is abundant in natural daylight (and phone screens) has long been thought to suppress melatonin production, with red light in contrast, actually helping signal the body to prepare for sleep (Figueiro et al., 2011). Despite this, new research from the University of Basel and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) may contradict this long-held belief. Still, when you consider the role of the SCN in detecting light, as well as many previous studies, it can still be concluded that reducing screen time and light exposure before bed can promote better sleep quality. The takeaway is that maximising exposure to natural light during the day and minimising exposure to artificial light in the evening is still generally recommended to reinforce your natural sleep-wake patterns.

Get to know your sleep.

The quality of sleep you get is essential for supporting your physical and mental health. Environmental factors, as well as duration, affect your sleep cycle and how refreshed and revitalised you’ll be when you wake up. REM sleep helps process emotions and cope with stress. Lack of REM sleep can increase irritability and emotional instability (Van der Helm et al., 2011). Learning how your sleep clocks-in can help you to plan your night-time recuperation. Learn more about your sleep here.

Play to Your Strengths

Recognising your own chronotype can help you to inform your schedules, potentially improving overall health and productivity. If possible, seek flexible work or study arrangements that allow you to operate according to your chronotype. This flexibility can reduce stress and improve productivity.

All said and done, our society is still fairly regimented around a standard schedule, and simply changing jobs isn’t an option for everyone. There is much that could be said about flexible schedules that accommodate individual circadian rhythms, which ultimately would foster a healthier, more productive population, but until then it’s important we keep on top of our sleep hygiene.

Reinforcing good habits is the best way to give us all the best chance of a well-rested sleep. For more information, or to book, get in touch with your AccessEAP Main Contact, or reach out via 1800 818 728.

__________________________________________________________________________

References

- Breus, M. J. (2016). The Power of When: Discover Your Chronotype--and the Best Time to Eat Lunch, Ask for a Raise, Have Sex, Write a Novel, Take Your Meds, and More. Little, Brown and Company.

- Coogan, A. N., & McGowan, N. M. (2017). A systematic review of circadian function, chronotype and chronotherapy in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 9(3), 129-147. Link to Article

- Giampietro, M., & Cavallera, G. M. (2007). Morning and evening types and creative thinking. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(3), 453-463. Link to Article

- Hartmann, T. (1996). Attention Deficit Disorder: A Different Perception. Underwood Books.

- Horne, J. A., & Ostberg, O. (1976). A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. International Journal of Chronobiology, 4(2), 97-110.

- Roenneberg, T., Wirz-Justice, A., & Merrow, M. (2003). Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 18(1), 80-90. Link to Article

- Baker, F. C., & Driver, H. S. (2007). Circadian rhythms, sleep, and the menstrual cycle. Sleep Medicine, 8(6), 613-622. Link to Article

- Bass, J., & Takahashi, J. S. (2010). Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science, 330(6009), 1349-1354.

- Cermakian, N., & Boivin, D. B. (2003). A molecular perspective of human circadian rhythm disorders. Brain Research Reviews, 42(3), 204-220.

- Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(4), 1232-1237. Link to Article

- Crowley, S. J., Acebo, C., & Carskadon, M. A. (2007). Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Medicine, 8(6), 602-612. Link to Article

- Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2009). Effect of light on human circadian physiology. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 4(2), 165-177. Link to Article

- Reppert, S. M., & Weaver, D. R. (2002). Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature, 418(6901), 935-941.

- Roenneberg, T., Kuehnle, T., Juda, M., Kantermann, T., Allebrandt, K., Gordijn, M., & Merrow, M. (2007). Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11(6), 429-438. Link to Article

- Samson, D. R., Crittenden, A. N., Mabulla, I. A., Mabulla, A. Z. P., & Nunn, C. L. (2017). Chronotype variation drives night-time sentinel-like behaviour in hunter–gatherers. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 284(1858), 20170967. Link to Article

- Sharkey, K. M., Fogg, L. F., & Eastman, C. I. (2001). Effects of melatonin administration on daytime sleep after simulated night shift work. Journal of Sleep Research, 10(3), 181-192. Link to Article

- Straif, K., Baan, R., Grosse, Y., Secretan, B., El Ghissassi, F., Bouvard, V., Altieri, A., Benbrahim-Tallaa, L., & Cogliano, V. (2007). Carcinogenicity of shift-work, painting, and fire-fighting. The Lancet Oncology, 8(12), 1065-1066. Link to Article

- Turek, F. W., Joshu, C., Kohsaka, A., Lin, E., Ivanova, G., McDearmon, E., et al. (2005). Obesity and metabolic syndrome in circadian Clock mutant mice. Science, 308(5724), 1043-1045.

- Waterhouse, J., Reilly, T., & Edwards, B. (2004). The stress of travel. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(10), 946-966.

- Wittmann, M., Dinich, J., Merrow, M., & Roenneberg, T. (2006). Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiology International, 23(1-2), 497-509.